My latest piece, The Middle Ages, is about why middle school sucks. Go read it (or watch the video above) and come back for a behind-the-scenes look.

The data

Last year, a data scientist at a company called Panorama Education emailed me to ask if I’d be interested in their data. They survey millions of K-12 student each year, they offered to share de-identified student-level data with me, as long as I agreed to protect the data and not de-identify the data.

I analyzed it every which way and found some interesting trends. But I couldn’t ignore the one big trend Panorama told me I’d see: When students hit the sixth grade, their feelings of belonging way down. When I worked in newsrooms and reported on education, sources would often refer to this middle school slump, but I never got around to writing about it. So, I thought, surely I’d find something else in the data worth writing about.

But I couldn’t stop thinking about this story about middle schoolers struggling. I started reading more and more about the topic, and found that scholars had been talking about how to educate pre-teen for more than 100 years. Reading through all this, I thought to myself: I wish I knew this in middle school.

Why it resonated with me

When I pick a Pudding story to work on, I tell myself the topic has to resonate with me. These stories take several months, and I never want to get halfway through a project and start feeling bored.

Well, I couldn’t stop thinking about this middle school story.

I went to a different school every year from first grade to fourth grade. I was forced to leave behind my favorite teachers, my best friends, and a familiar school building. But between fourth and fifth grade, we stayed in the same house. That meant fifth grade was the first time I ever got to start a new year with existing friends. I thought it could only get better from here.

I thought sixth grade would be amazing.

That wasn’t true. Throughout sixth grade, I felt like my friends weren’t satisfied with be as a friend, because they constantly shunned me for new friends. I felt like my teachers didn’t really care about me. And every time I felt like I was getting settled in, I’d experience a traumatizing social interaction that made me wonder whether something was wrong with me. I just wanted friends who cared about me—but I didn’t know how to make that happen.

I’d spent most childhood surviving loneliness, instability, and social discomfort. So I knew how to survive this. I got into jazz piano. I got into playing Pokemon on my Gameboy. I spent a lot of time throwing a baseball at a net in my backyard. I receded into my own world. And if it was anything like the rest of my life, this era would pass.

So I white-knuckled myself through middle school. And eventually things got much better in high school, better through adulthood, and so on.

But, again: Why didn’t anyone tell me that middle school was going to be so hard—and that it wasn’t my fault?

The concept

This story has been told before. I’m not uncovering some huge phenomenon that will change the future of education. In fact, this story sums up a lot of what education scholars, school administrators, and child psychologists have been talking about since at least the 1890s.

But I wanted to tell this story to a middle schooler. (In fact, if you’re a middle school teacher or parent and you shared it with your kid, please tell me!)

It’s exceedingly hard to break down data and academic literature into a story that’s accessible to the layperson, let alone middle schoolers. But I worked through the piece, beat by beat, to try to keep it accessible without losing nuance.

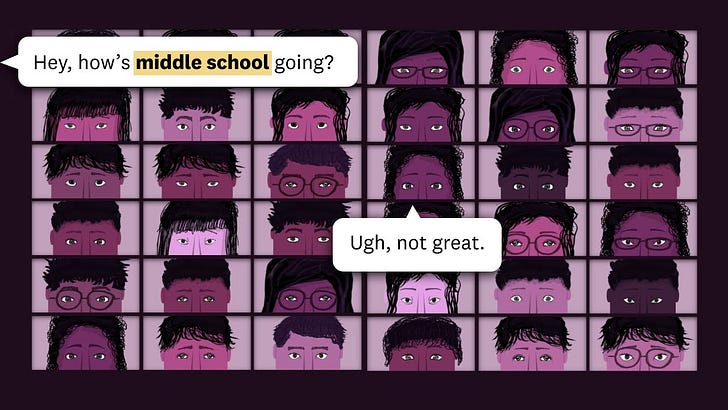

Early on, I had the idea of visualizing the data with a whole bunch of eyes that represent students, because I thought it would drive home the point that these aren’t just broad data points, but rather actual kids:

Humans have a very strong connection to things that look like eyes. In fact, it’s often how we recognize other people. So I knew the eyes had to be expressive.

Well, guess who struggles to draw realistic eyes?

I also draw a bunch of varying hairstyles, thinking that I’d assign some to younger kids and some to older kids.

And then I made a component (I’m using Svelte) that generates a bunch of faces for kids. I made some adjustments for age—namely, bigger eyes for younger students.

Now, this seems easy enough, but I had a few hours of trouble getting all the features in the right place. It made for some fun mistakes.

The big revelation: Make the story a conversation

With all this setup, I started making a scrolly story.

I have to be honest: I’m trying to find other ways to tell interactive stories. My last piece, Sitter and Standers, replaces scrolling with a “next” button. But at the end of the day, it’s still a fancy slideshow.

One thing that happens when I tell a story with floating text boxes in a scrolly is that I tend to write with a sort of omniscient tone. That’s exactly what I didn’t want to do in a story written, in part, for middle schoolers. So I went back to my script and started to rewrite the piece in a more accessible, preteen-friendly tone. But that just felt condescending.

So I asked myself: How would I tell this story directly to a middle schooler? Well, I’d go into a middle school, ask them these survey questions, and show them the results. That way they could see for themselves what was happening, and then we could talk about it.

That was my ah-ha moment: I should just talk to the kids on the screen.

I really like the video

I’ve been making accompanying videos for each of my Pudding stories. Usually, I start with the interactive and turn it into a video. But when I came up with the concept of talking to the kids on the screen, I knew it would make a kick-ass video.

I think it turned out quite nicely.

I particularly like the sections where I explain the brain development. The simple line-based motion graphics are just enough to get across the concept, almost like a teacher writing on a blackboard while giving a lecture.

I’m also quite proud of the music. At the end of last year, I told myself I wanted to make my own music. I bought a MIDI keyboard, learned how to use Ableton Live, and relearned some of the music theory I’d forgotten in the past 25 years.

(A quick aside: I’m hugely grateful for my parents, who put me in piano classes when I was a kid. When I showed interest in jazz piano, they let me take jazz piano classes. And in middle school, when my mom attended the local junior college for nursing school, she brought me to school with her and enrolled me in a music composition class. Recently, my mom started taking classes to learn piano, so my brother and I bought her a piano; she told me she practices Hanon—basically, piano agility exercises—for 30 minutes each day.)

The deciphering the ending

The end of this piece is slightly cryptic, so here’s what I was thinking.

I’m immensely sad with what’s happening to my country, the United States of America. Growing up as an immigrant kid, I heard so much from my family about how great this country is. We were the good guys, or at least that mattered to us.

But now, the bullies from our middle school days are in charge—and those with the power to stop them are letting it happen.

I hope the middle schoolers represented in the story can inherit a more empathetic world than the one we’re handing them.

The story is so touching. It reminds me of my middle school time. I love this post too! It's so inspiring to read your creative process. And I can't believe that you also did the music!

This was stellar. My heart goes out to students nowadays. We really never do enough for them.

As always loved the behind the scenes. The story was spectacular